Category: Symphonic / Orchestral , Recordings

The music on this CD seeks to build bridges: to the great composers Mozart and Beethoven of our own tradition as well as to the music of Asia. This recording is also a portrait of the Jena Philharmonic Orchestra, an outstanding ensemble with a youthful joy in experimentation... with its Principal Conductor Simon Gaudenz. And there are two internationally renowned soloists. Juliana Koch is an ARD prizewinner and solo oboist of the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Sir Simon Rattle. Wu Wei is the world’s leading exponent of the Sheng, a traditional Chinese instrument. I am fascinated by his artistry and have composed five concertos for him.

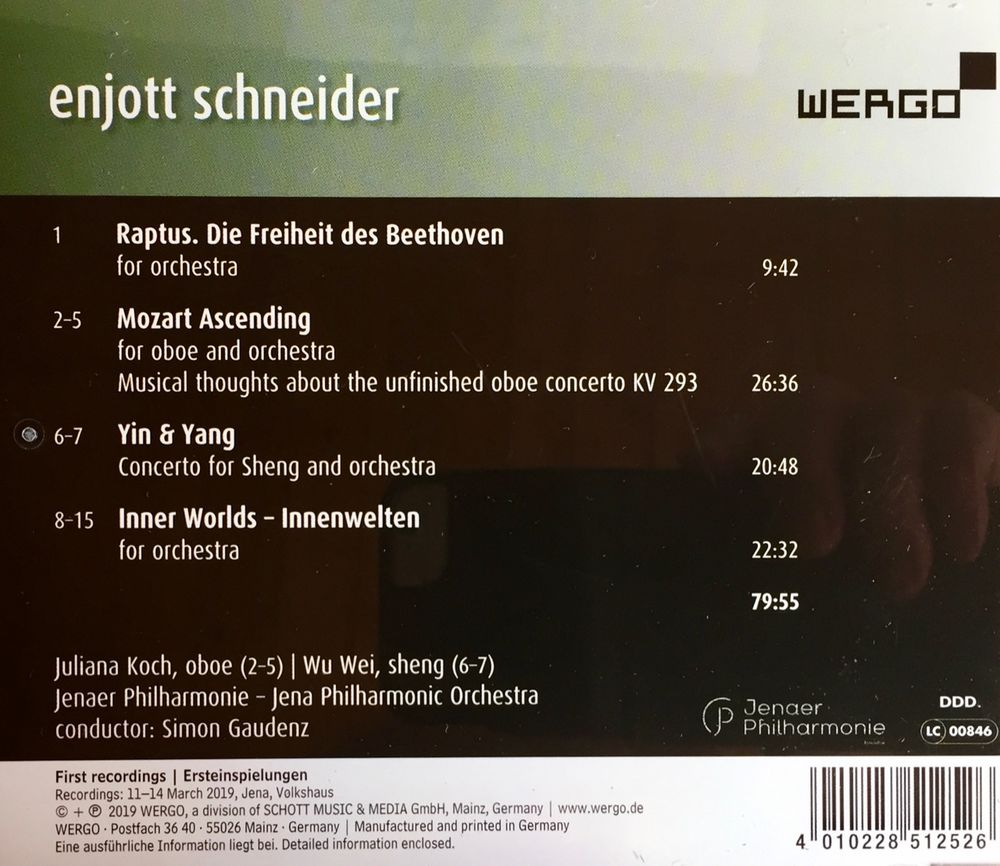

Movements: RAPTUS. DIE FREIHEIT DES BEETHOVEN für Orchester

MOZART ASCENDING for oboe and orchestra

Musical thoughts about the infinished oboe concerto KV 293

- Prologue “As fate willed” - - Concerto Allegro

- Adagio. „Bitterness of Life” - Epilogue „Mozart ascending“

YIN & YANG. CONCERTO for Sheng and orchestra

- Yin

- Yang

INNER WORLDS – INNENWELTEN for orchestra

Sinfonische Stimmungsmeälde aus Oper Bahnwärter Thiel

- Shadows of the Past - Schatten der Vergangenheit

- Dark Clouds. - Dunkle Wolken

- Solitude in the Forest - Waldeinsamkeiten

- Intermezzo of unrealities - Unwirkliches Intermezzo

- Inner Worlds - Innenwelten

- Peace of Nature - Friede der Natur

- Accident and Desaster - Unfall und Katastrophe

- Moonlit Night and madness – Mondnacht und Wahnsinn

© Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG (2-5, 8-15) / © Ries & Erler Musikverlag Berlin (1, 6+7)

Introduction: The music on this CD seeks to build bridges: to the great composers Mozart and Beethoven of our own tradition as well as to the music of Asia. This recording is also a portrait of the Jena Philharmonic Orchestra, an outstanding ensemble with a youthful joy in experimentation. Under the direction of its Principal Conductor Simon Gaudenz, it has become a remarkable group of musicians with whom I am delighted to collaborate. Other highlights here are the two internationally renowned soloists. Juliana Koch is an ARD prizewinner and solo oboist of the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Sir Simon Rattle. Wu Wei is the world’s leading exponent of the Sheng, a traditional Chinese instrument. I am fascinated by his artistry and have composed five concertos for him.

Additional remarks: Raptus. Die Freiheit des Beethoven [Rapture. Beethoven’s Freedom] has been chosen by the German Music Council as a required work for the German Orchestral Competition in the Beethoven anniversary year of 2020. Helene von Breuning, a mentor and maternal figure to the young Beethoven, used the Latin term “raptus” to describe his attacks of rage, embitterment, and despair as a state of rapture. Beethoven himself used the term “raptus” throughout his life in a self-deprecating way to characterize his disruptive episodes. His personality and his work as a composer were profoundly shaped by these dissonances and stark contrasts.

My orchestra piece deals with such categorical discontinuity, exploring the contrast between Beethoven’s “heroic” early style and his cryptic and lyrical late works. In both cases, he was concerned with the central subject of freedom. As early as 1793, he wrote, “Love freedom above all else” in the family registry of Elisabeth Vocke, and in 1819 he described the goal of art as “freedom alone and going further”. In the spirit of Friedrich Schiller and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Beethoven was initially concerned with the subjective freedom of the “Sturm und Drang” era, with its anti-feudal political convictions as represented by Napoleon and his glorious victories. Beethoven’s music almost demanded attention with its previously unheard depictions of power and violence. Inspired by the music of the French Revolution, his expressions of pathos, conquest, and creative energy were almost boundless. But at the latest with the onset of his deafness and the Heiligenstadt Testament, his self-identification as a “hero” was gradually replaced by a more modest and humble personality: spirituality, celestial realms, religious transcendence, gratitude, and love of nature became the symbols of a new way of life. Instead of battles with Fate, we now sense rever- ence and an almost cosmic love divorced from material concerns. A simple song of thanksgiving became the goal of his creative energy. This is explicitly the case in the “Shepherd’s Song: Cheerful and Thankful Feelings” in the Pastoral Symphony, op. 68, and in the third movement of the A minor String Quartet, op. 132: “Holy Song of Thanksgiving to the Deity from a Convalescent, in the Lydian Mode.” This spirit of wordless devotion can be found in all of Beethoven’s late works, especially in the string quartets and piano sonatas; the Arietta in op. 111 is especially beautiful.

Raptus traces these contrasts and places a number of quotations from Beethoven’s cosmos in a new context: in the first half of the piece, passages from the “Eroica” as well as the Fifth and Ninth symphonies stand alongside a motif made up of two eighth notes derived from the syllabic rhythm of the word “rap-tus”. A lyrical spirit of gratitude dominates in the second half of my piece. The storm sequence at the end should be understood onomatopoeically: Anselm Hüttenbrennen wrote about the final moments of Beethoven’s life, when the composer raised his right fist against the sounds of a thunderstorm with sleet, hail, lightning, and thunder – and then died. The end of the piece, however, turns to the riddle canon WoO 198, which Beethoven dictated to Karl Holz in December of 1826: “We are all fools, but each a different kind.”

MOZART ASCENDING for oboe and orchestra is a musical reflection on his unfinished oboe concerto KV 293. Mozart’s short fragment is beautiful, but this only deepens the mystery: why did such heavenly music remain unfinished, and is this related in some way to the composer’s life? The question remains: who was this Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who still confronts us with unparalleled contradictions, dark unsolvable riddles, and an aura of genius that can only be described as otherworldly?

Mozart Ascending is involved with exactly this question. Emotions and con- trasts are built up around the original music; associations are allowed to come and go. A cosmic power beyond human comprehension seems to have presided over Mozart’s life. Let us simply call it Fate or Destiny. For me, this Destiny has a name: Leopold! The father’s harsh hand and strenuous discipline were the dark side that belongs inexorably to the phenomenon of the Wunderkind: the brighter the light – for which we are all so grateful – the darker the shadows in the background. In his seventh Duino Elegy, Rainer Maria Rilke says, “Do not think that Fate is more than the distilla- tion of childhood”, and Rilke’s comment that “Art is childhood” expresses the importance of the childhood years for the course of a human life. Leopold? Is it not possible that the younger Mozart’s escape into beauty and immaterial jollity, the attractions to women and gambling, even the transcendence and the ascension into heavenly spheres were all simply attempts to establish a world of his own in opposition to the functional realism and dominance of the father principle? This sense of Destiny seems to me to be the subtext and hidden key to all of Mozart’s works. Mozart Ascending is an attempt to make such a subtext emo- tionally accessible.

Peter Schaffer’s Amadeus, filmed by Milos Forman, argues that the avenging “Commendatore” in Don Giovanni symbolizes the subjugation Mozart experi- enced with his father, who controlled him throughout his life as an internalized sense of conscience and guilt. This makes the musical quotations from Don Giovanni in the freely associated development section of the oboe concerto particularly notable.

Based on evidence such as the paper used for the manuscript, the fragmentary KV 293 seems to have been composed in the autumn of 1778, a particularly dark and fateful period in Mozart’s life. Following his banishment by the Archbishop of Salzburg, he traveled in the spring to Paris with his mother – his first trip without his father! – to seek work as an independent artist. The results were sobering. In addition to the lack of professional success, his mother died in Paris on 3 July, a staggering and catastrophic turning point in Mozart’s life. Was the ensuing composition of the Oboe Concerto in F major an attempt to flee into a world beyond this brutal reality? Like the lark in Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending, Mozart’s music rises into ethereal realms.

YIN & YANG – The Concerto for sheng and orchestra was written in 2017 for the “Asia-Siberia-Europe” festival in Krasnoyarsk and was premiered there by Wu Wei, with Simon Gaudenz conducting. The piece refers to the more than 2000- year-old Taoist concept that there is no true duality, since seeming contrasts are in a state of constant flux; the paired elements are inseparably united. The two most common symbols of Yin and Yang are the “Taichi” symbol with two inter- twined black and white fish and the “Hotu” symbol with two spiral galaxies, also

intertwined and shown in black and white. The sum of the black and white ele- ments is always constant. The philosophical principle teaches that negative energy cannot grow endlessly, but will eventually become positive. In the same way, the wise person comes to realize that happiness cannot last, but must eventually return to darkness.

Yin is considered to be female, passive, and soft: rest, darkness, the dark moon, coldness, and death. Yang is male, hard, and active: work, life, the full moon, brightness, and heat.

INNENWELTEN - INNERWORLDS presents eight instrumental interludes from my opera, Bahnwärter Thiel (based on the novella by Nobel laureate Gerhart Hauptmann). Thiel is a tragic figure caught up in a social drama similar to that of Büchner’s Woyzeck: hypersensitive, full of fears and inner visions, but taciturn and not given to overt expression. His existence gradually collapses under the weight of societal pressures: his son from his first marriage is killed accident; in a fit of grieving rage, Thiel then murders his second wife son and is committed to an asylum. Innerworlds presents an expansive al panorama in which the depiction of “nature” plays a decisive role, the “Sea Interludes” from Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes.

English translation by John Patrick Thomas and W. Richard Rieves

Records: WERGO 5125 2 distributed by Naxos. LC 00846, 2019

Performers on recording: Juliana Koch, Oboe (2-5)

Wu Wei, Sheng (6,7)

Jenaer Philharmonie – The Jena Philharmonic (1, 7-11)

conductor: Simon Gaudenz

Ersteinspielungen / First recordings

Recordings:

11.3. – 14.3.2019 in Jena, Volkshaus concert hall

Recording & Editing: Pegasus Audio

Florian B. Schmidt – Hannes Baier